Contents

- 1 Learn More About “Constructing Hope: Ukraine”

- 1.1 Interior Design: Can you tell us about the ways you are each connected to Ukraine and how that impacted the exhibition?

- 1.2 ID: What were you most considering when bringing this group of practitioners together in one exhibition?

- 1.3 ID: What were the concepts that drove the design of the exhibition, including its physical and thematic arrangement?

- 1.4 ID: Could each of you tell us about a practitioner or element that felt especially meaningful?

- 1.5 ID: Can you explain the story behind the full-scale prototype of a bed designed by the Ukrainian NGO MetaLab?

- 1.6 ID: What can you tell us about the Oberih publication and how Understructures brought it to life?

- 1.7 ID: And how do the graphics—inspired by taped windows—by Aliona Solomadina, enhance the exhibit and the story it aims to tell?

- 1.8 ID: Shigeru Ban’s Paper Partition System is also included. Can you tell us about how local firms made use of the system and if it can point towards how international firms can potentially support this ongoing effort?

- 1.9 ID: What surprised you as you put together this exhibition?

- 1.10 ID: The message here is a hopeful one. How did putting this together impact your perspective on the war or your own outlook?

Constructing Hope: Ukraine is on view through September 3rd at the Center for Architecture in New York. Photography by Matthew Carasella.

On view at the Center for Architecture in New York, the exhibition “Constructing Hope: Ukraine” presents the work of over one dozen practitioners using architectural concepts and strategies in support of Ukraine. The show illustrates that more than two years after the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine, local organizations and multidisciplinary firms have mounted creative and inspiring responses to support Ukrainian resistance and reconstruction. Bringing together a range of projects, the exhibition sheds light on how architecture can support communities with thoughtful and groundbreaking strategies.

“Constructing Hope,” on view through September 3 at 536 LaGuardia Place, was curated by Ashley Bigham, Sasha Topolnytska, and Betty Roytburd. Ashley Bigham is an associate professor at the Knowlton School of Architecture and co-director of Outpost Office. Bigham is also a collaborative partner and visiting faculty at the Kharkiv School of Architecture in Ukraine. Sasha Topolnytska, a Ukrainian-born and American-trained architectural designer and educator, is currently an adjunct professor at Spitzer School of Architecture at the City College of New York and a founder of Farmmm Studio. Betty Roytburd, a Ukrainian-born artist, activist and mental health worker living and working in New York City, co-founded SPILKA NGO and is currently pursuing a Master of Social Work at the Silberman School of Social Work at Hunter College.

Interior Design asked the three curators to discuss the exhibition’s themes and components, as well as its message to the world.

Betty Roytburd (left), Sasha Topolnytska (center), and Ashley Bigham (right), curators of the exhibition Constructing Hope: Ukraine. Photography by Jenna Bascom.

Learn More About “Constructing Hope: Ukraine”

Constructing Hope: Ukraine is on view through September 3rd at the Center for Architecture in New York. Photography by Matthew Carasella.

Interior Design: Can you tell us about the ways you are each connected to Ukraine and how that impacted the exhibition?

Sasha Topolnytska: I was born in Kyiv, Ukraine, and moved to the United States when I was 17. I studied and trained as an architect here, and even started a family. With most of my adult life in the U.S., my life in Ukraine felt almost distant. However, the invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, has been one of the most traumatic and pivoting events of my life. It reminded me how important my Ukrainian culture is to me and that preserving and sharing it with others is essential, especially when it is actively under the threat of destruction.

Betty Roytburd: I was born in Odesa, Ukraine, and moved to New York when I was 10. Since then, I have been consistently traveling to Ukraine to spend time with family, friends, and loved ones who continue to live and work in Ukraine. At the start of the full-scale invasion, together with a group of other Ukrainians and friends, I co-founded a nonprofit organization that hosted dinners, music shows, and cultural events to raise money for mutual aid and volunteer efforts in Ukraine.

Ashley Bigham: I first traveled to Ukraine in 2008 as an undergraduate architecture student. I quickly became fascinated with the architecture, and took it upon myself to study a part of the world frequently overlooked in American architectural education. In 2014, I moved to Ukraine as a Fulbright Fellow to pursue a year of research that coincided with the Revolution of Dignity. Witnessing the revolution first-hand helped me understand Ukraine’s long fight for democracy, freedom, and dignity, and solidified my desire to support that fight. In the years following, I partnered with Ukrainian architecture schools and taught travel courses where American architecture students could visit Ukraine. During the past decade, it has remained my mission to share the incredible artistic achievements of Ukrainian culture with the world.

ID: What were you most considering when bringing this group of practitioners together in one exhibition?

ST: Since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, famous international architects have proposed grand, sweeping ideas for rebuilding Ukrainian cities like Kharkiv, which has been under continuous attack since the start of the invasion. While it is essential to bring international practitioners to the table in a conversation about reconstruction efforts, we believe that the most critical work is being done by grassroots initiatives inside and outside Ukraine, led by Ukrainians, often in collaboration with international partners. In our exhibition, we focus on collaborative community-led projects that highlight Ukrainian culture and the importance of preserving it in every future reconstruction project. We invite international audiences to learn more about Ukrainian design culture and the importance of preserving it in any rebuilding efforts.

The exhibition includes over a dozen participants applying architectural thinking to support reconstruction efforts within Ukraine. Photography by Matthew Carasella.

ID: What were the concepts that drove the design of the exhibition, including its physical and thematic arrangement?

AB: It was always vital for us to balance the ideas of hope with the realities of war in Ukraine. In addition, the exhibition’s content should be accessible to a diverse audience who may know very little about Ukraine. We quickly realized that hope was not an abstract concept or a choice; it is the actions of designers and citizens that provide the hope necessary to move forward. The idea that all people, no matter their training or physical ability, have something to contribute to war recovery efforts is a powerful and universal narrative in the exhibition.

ID: Could each of you tell us about a practitioner or element that felt especially meaningful?

ST: Repair Together is a self-organized grassroots organization engaging volunteers worldwide to rebuild villages and homes in the Chernihiv region. Rave Toloka is their initiative during which volunteers clean up rubble caused by Russian aggression to the music of DJ sets. The title of this project is based on the ancient Ukrainian tradition of mutual assistance called “toloka,” which involves people gathering and working together to address urgent community needs. They also have been fixing people’s damaged homes and constructing new ones. Most of the team members and volunteers of Repair Together do not come from architectural or construction backgrounds. Yet, they are actively using architectural strategies to respond to the present needs of their community.

BR: It was crucial for us to communicate to our audiences how hope is ingrained in virtually every decision involved in reconstruction projects amidst ongoing destruction. This is powerfully illustrated by the work of Livyj Bereh (Left Bank), a volunteer organization led by three friends from Kyiv: Vlad Sharapa, a 38-year-old former construction worker, Ihor Okuniev, a 35-year-old multimedia artist, and Ksenia Kalmus, a 36-year-old florist. Livyj Bereh integrates immediate aid with long-term vision, creatively documenting their work through photography and historical archiving. Having originally come together to distribute mutual aid, they have since focused on restoring roofs in war-torn villages, supporting regional economies by employing and training local workers and preserving Ukrainian cultural heritage. Their approach unites urgent actions with poetic attention to detail. Members Vladyslav and Ihor have recently enlisted in the Ukrainian armed forces.

AB: The exhibition includes two chair prototypes designed by architecture students from the Kharkiv School of Architecture, each responding to different needs brought on by the war. One of the chairs is compact and lightweight so that it can be mobile as people move in and out of bomb shelters, and the other is reconfigurable to help adapt to the many different needs of students during the day, including resting and studying. These students are pursuing a degree in architecture, despite the difficulty of war, because they are dedicated to learning the skills and knowledge they will need to rebuild their society. Their optimism, hard work, and determination inspire me daily.

Repair Together’s Rave Toloka initative. Photography by Oleksiy Ushakov/UNDP Ukraine /Courtesy of Repair Together.

ID: Can you explain the story behind the full-scale prototype of a bed designed by the Ukrainian NGO MetaLab?

ST: The gallery has a beautiful connection to the street, with a large storefront looking into a double-height gallery space. We wanted to take advantage of this unique view and suspend a modular bed system designed by the Ukrainian NGO MetaLab, which provides temporary emergency accommodation for internally displaced people in Western Ukraine. By separating the bed into separate pieces in the double-height gallery space, similar to the architectural representation technique of exploded isometric drawing, we wanted to show the prototype’s simple yet clever design.

ID: What can you tell us about the Oberih publication and how Understructures brought it to life?

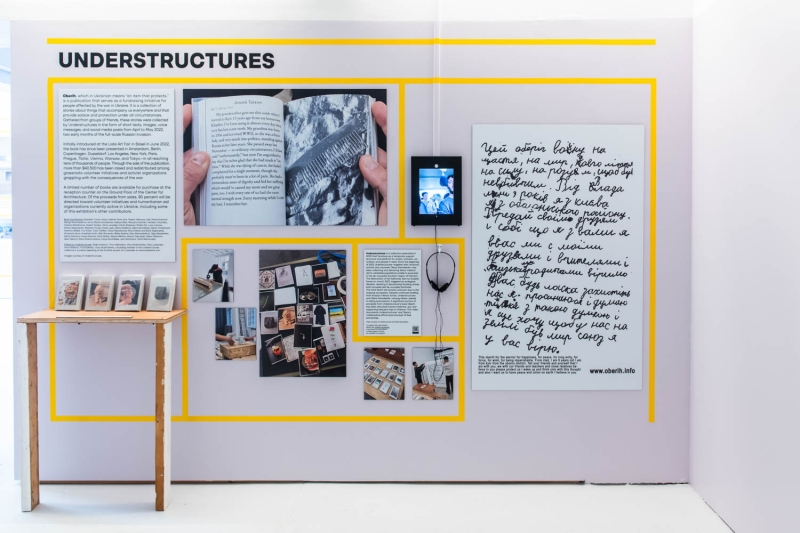

BR: Oberih, which translates from Ukrainian as “an item that protects,” is the name of a publication by Understructures, a collective of friends who are artists, architects, and designers. The book features a collection of personal stories about objects that offer solace and protection, gathered during the early months of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. These stories—initially shared as short texts, images, voice messages, and social media posts—beautifully capture how we find comfort in the symbols of home during times of crisis. Since 2022, Oberih has raised over $40,500 for grassroots volunteer efforts. Since early 2023, Understructures, alongside Ukrainian activist Olena Samoilenko, has been delivering crucial medical aid to vulnerable populations unable to evacuate in the de-occupied Southern region of Kherson, which has been devastated by flooding and ongoing Russian attacks. Victor Gluschenko, a founding member of Understructures, is currently on the frontline as part of a volunteer air reconnaissance unit. Many of the initiatives funded by Oberih are featured in this exhibition, highlighting how creative collaboration can bring hope and protection in the darkest times.

Oberih are publications that document experiences of the war through photographs of meaningful objects, by Ukranian collective Understructures working with LC Queisser Gallery. Photography by Matthew Carasella.

ID: And how do the graphics—inspired by taped windows—by Aliona Solomadina, enhance the exhibit and the story it aims to tell?

ST: The taped windows, typically found throughout Ukraine during the ongoing war, inspired the graphic identity for the exhibition. Ukrainian people often tape their windows in intricate, crisscross patterns to protect their homes from shattering glass during explosions. This practical solution has become a visible symbol of resistance in Ukraine and one we used as an organizing design feature in the exhibition.

ID: Shigeru Ban’s Paper Partition System is also included. Can you tell us about how local firms made use of the system and if it can point towards how international firms can potentially support this ongoing effort?

AB: In the first weeks of the war, Shigeru Ban contacted designers in Ukraine to share his design for lightweight partition systems made of cardboard. Ukrainian architects then adapted his system to construct temporary shelters in gymnasiums or large halls to house internally displaced people. They also modified the designs to use surplus local building materials like metal construction fencing. It’s important to note that Ban first designed the Paper Partition System following a devastating earthquake in Japan. Similarly, we hope that others can utilize design ideas featured in our exhibition to respond to other humanitarian disasters. Unfortunately, we know that many people worldwide currently need life-saving shelter and spaces of dignity. Design is at its best when shared widely and adapted locally.

The show’s graphics by Aliona Solomadina were inspired by the war-time taped windows currently seen throughout the country. Photography by Matthew Carasella.

ID: What surprised you as you put together this exhibition?

BR: As an artist and mental health worker, working on this exhibition offered me a unique opportunity to engage with architecture in a deeply immersive way. I have been inspired to learn about ways architecture and storytelling both involve creating and shaping worlds. Working on this project, I was particularly struck by the connections between various disciplines in the work of the architects, artists, and creators. The creative ways the participating initiatives tackle questions related to mental health in the communities they are serving have been something I continue to reflect on and think about. The process of presenting the projects in this exhibition has highlighted the multifaceted and interdisciplinary nature of recovery work and prompted me to consider how different elements in our daily lives can truly make a place feel like home for every individual.

ID: The message here is a hopeful one. How did putting this together impact your perspective on the war or your own outlook?

BR: The work showcased in this exhibition is inspiring on multiple levels. It shifts the perspective from viewing Ukraine solely as a place of conflict to recognizing it as a place with much to offer and share. By employing skill and knowledge exchange, these projects illustrate the profound impact of collaboration and resilience. Mutual aid projects also build solidarity. Much of the work demonstrates that those on the front lines of a crisis have the best wisdom to solve the problems and that collective action is the way forward. On a larger scale, my greatest hope is that these approaches will inspire societal change and highlight the power of ingenuity and collectives, both in small-scale initiatives and in fostering a broader sense of unity, solidarity, and support in Ukraine and internationally.

Livyj Bereh (“Left Bank” in Ukrainian) is a volunteer organization whose initiatives include rebuilding structures destroyed by war. Photography by Matthew Carasella.