Contents

- 1 Zohra Opoku Creates Textile Art Exploring Personal Identity

- 1.1 Interior Design: Describe your journey as a textile artist.

- 1.2 ID: You studied fashion earlier on; what was it like gravitating into art fully and working with brands?

- 1.3 ID: When did you fully begin to explore your textile practice?

- 1.4 ID: You were born and raised in Germany and later came back to Ghana after many years. What was that like for you?

- 1.5 ID: You’ve been in Ghana for more than a decade now. How has living here boosted your creative energy?

- 1.6 ID: You work with photography and archival images, which shape your textiles. Would you say it comes from your deepest creative desire to identify first as a fashion designer before an artist?

- 1.7 ID: You use a lot of vintage fabrics in your work and also adopt fashion techniques like embroidery and stitches. How did you come about it?

- 1.8 ID: What philosophy have you basked on that has shaped your practice and journey as an artist?

- 1.9 ID: What are you currently working on at the moment? What’s the project about?

Thinking Historically in the Present, 2023. Installation View 3.

In Zohra Opoku’s creative world, anything is possible and she uses textiles to bring these possibilities to life—combining artistic mediums like photography and fashion techniques, including hand stitching and embroidery, to enable her final process of screen printing.

Opoku’s textile adoption comes from her graduate studies in fashion, but it also comes from a memory of watching her mother and grandmother work their way with the sewing machine and handcrafting most of their pieces. Crafting textiles became a practice she paired with her love for photography and, for more than two decades, she has continued to combine both mediums to honor the numerous stories that appeal to her imagination.

Opoku creates with the intention to investigate, emphasizing the historical, economical and political perspective of Ghana, and how this influences its contemporary society. Sometimes, she interweaves personal accounts. Her project “Unraveled Threads” unveils a collection of archival portraits of her father as an Asante King, wearing Ghana’s popular fabric kente and printed alongside her German mother, between freestyle drawings and a dance of hand stitches.

Interior Design talked with the textile designer about her artistic journey, growing up in Germany, and why she loves living in Accra, Ghana.

Zohra Opoku. Photography by Nii Odzenma.

Zohra Opoku Creates Textile Art Exploring Personal Identity

Thinking Historically in the Present, 2023. Installation View 3.

Interior Design: Describe your journey as a textile artist.

Zohra Opoku: I was always an artist, as my creative output during my childhood was immense. I have this memory from when I was two years old, which my mom still gets impressed over that I can recall, where we had visited her artist friend Holger in his garden. And while we were walking through his studio, I saw these huge canvases leaning against the wall, which seemed like giants to me. I will never forget how I loved to inhale the scent of the oil paint and was fascinated by the energy in that house. Coming outside into the garden, there were strange but interesting people sitting around the table with some little sculptures, which Holger was working on. That was a big moment of joy, which still gives me an emotional feeling of fulfillment.

I have since then been obsessed with drawing, painting, dancing, photography, sports, Capoeira and fashion design. When I started studying, I ended up developing many skills and fully exploring the creative world. I believe this is why I can work in between mediums fluently today.

ID: You studied fashion earlier on; what was it like gravitating into art fully and working with brands?

ZO: Textile and fashion became part of my DNA, as it was so strongly represented through the handcrafts in my family and through the need to design my own clothes as a teenager—I grew up in a rather gray and uninspiring environment of the former German Democratic Republic (GDR) with no sense and access to vibrant clothing designs. Besides not having experienced people of color and a way to reflect my African side, it ended up becoming a search for identity and kept calling me to investigate it through my camera lens and textile printing.

ID: When did you fully begin to explore your textile practice?

ZO: Working with textiles came back to me strongly when I started living in Ghana. Everything became textile for me—the meanings, histories, and backgrounds that I wouldn’t really feel or be able to touch on in Germany, or understand. Even if I would want to dive into the same topics I’m touching on, it’s just not the same energy. It’s like once you are in Ghana, Ghana becomes you and you become Ghana. I was also able to articulate my family heritage, my emotions within my identity, using Ghanaian symbolism and traditions.

The artist with her work at Suite Berlin, 2024.

Ghana continues to shape Opoku’s art, offering endless inspiration.

ID: You were born and raised in Germany and later came back to Ghana after many years. What was that like for you?

ZO: My Ghanaian father and my East German mother met in the summer of 1975 in Halle in the former GDR, where they both were studying. I was born one year later. We lived behind the wall of communist East Germany. Unfortunately, my father had to leave the GDR and return to Ghana. My mother could not follow and was left behind. For me, it became the remarkable story of my life—which influenced my whole being—and inspired my decision later to become an artist and to assimilate belonging and identity into my practice.

ID: You’ve been in Ghana for more than a decade now. How has living here boosted your creative energy?

ZO: Ghana has this way of infiltrating your DNA. I have never had such a strong connection to another place, and this inspiration has given life to me and informed my work. My art wouldn’t have become what it is today if I had not have moved to Ghana, as I needed the freedom to do something that does not make sense to others, but to me. I created art from my desire to inspire, dig deeper, understand humanity and most importantly, to understand myself, specifically connecting to my heritage, the Asante culture in Ghana. It molded who I am today, and I can call myself, with certainty, an artist.

ID: You work with photography and archival images, which shape your textiles. Would you say it comes from your deepest creative desire to identify first as a fashion designer before an artist?

ZO: No, not at all. I became an artist because I identify as an artist first. As much as each of my works reflect on the lives of people, I also express these stories with figurative abstractions. Is it an enigmatic means to encourage viewers to dissect your work?

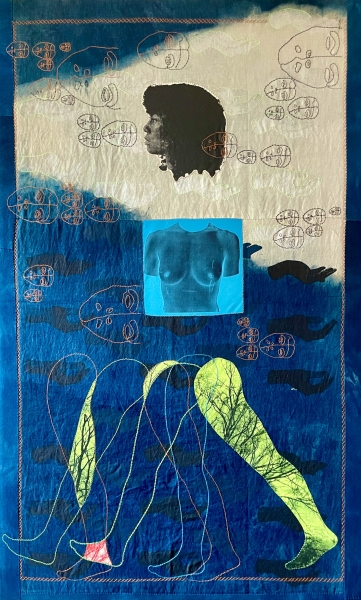

From I Have Arisen.

From I Have Arisen… Part 2.

ID: You use a lot of vintage fabrics in your work and also adopt fashion techniques like embroidery and stitches. How did you come about it?

ZO: It was such an organic process. Growing up, my mom was always sitting at the sewing machine or knitting; my grandmother was doing embroidery and knitting as well. Handcrafting was present in my upbringing, and painting and drawing came naturally to me. Also, textiles were always around. Later, when I studied fashion, I realized I was already done with it; I ended up spending more time in the photo department than in the fashion department. I was always exploring black-and-white photography because it connected me to my childhood—all the archival photographs of my mom and my grandparents in our photo albums were in black and white.

ID: What philosophy have you basked on that has shaped your practice and journey as an artist?

ZO: The question of identity was the starting point in my work, as an artist deeply rooted in my family lineage on both my German and my Ghanaian side. Through my studies, I have been able to articulate my innate familial connection to Ghanaian symbolism, and traditionally produced cloth—such as the Kente cloth which continuously inspires me and plays a large role in my imagery. I also love to be inspired by my natural environment in Ghana—through which I feel impulses of home, picturing sacred places and the fluidity of identity. This manifests in my work through images with backgrounds of rich vegetation, supporting also the idea of disguise and protection. I also incorporate mainly traditional dress codes worn by my Ghanaian siblings and myself.

ID: What are you currently working on at the moment? What’s the project about?

ZO: I am currently working on my screen print series “Give me back my Black dolls,” which explores ideas with references from psychology experiments conducted in the 1940s that used dolls to study children’s attitudes about race. The project is in three phases including research, workshops, and exhibition. During the research phase in 2022, conversations, connections, collections and exchanges were made with importers and retailers of dolls, different demographics of children and their parents. Due to the success of the research, we continued with the workshops, and this year, we started with the development of the artworks. One of the works will represent 200 dolls imported from China and dipped in ink inspired by the German children’s book Struwwelpeter, and also referring to traditional West African fabric dyeing.

13th Edition, Berlin Art Week 2024.

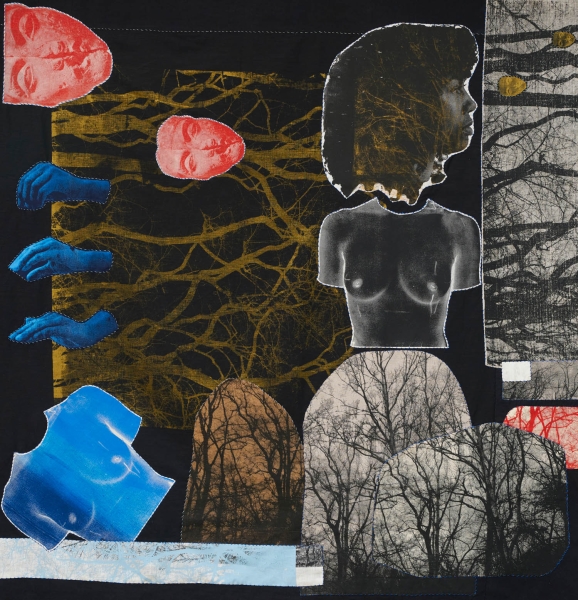

From The Myths of Eternal Life.