Contents

- 1 Get To Know Eliza Redmann Of Folded Poetry

- 1.1 Interior Design: Let’s start with the name of your studio, Folded Poetry. What do these words mean to you?

- 1.2 ID: I understand your recent work stems from a serious car accident that left you with a brain injury. Could you share more about how this event shifted your creative process?

- 1.3 ID: How do you translate the “swimming” images you often see into sculpture and acoustical art? What materials do you gravitate to?

- 1.4 ID: What led you to pursue architecture, initially? What are some of your earliest memories of design?

- 1.5 ID: You’ve described your art as “a child of the pandemic.” In what ways did the pandemic shape your work?

- 1.6 ID: Let’s talk about one of your recent collections. What led you to collaborate with Unika Vaev on acoustic products and what do you look for in a design partnership?

- 1.7 ID: Acoustics seem especially meaningful for you, given your injury. Could you share more about how you experience sound in spaces and how that impacts your work?

- 1.8 ID: When navigating spaces post-injury, what do you feel are some of the biggest opportunities to create more inclusive design?

- 1.9 ID: Do you consider your work as a form of activism?

- 1.10 ID: What’s your dream project? If you could create anything, what would it be?

Cassilhaus.

Eliza Redmann, founder of Folded Poetry, a design studio in Durham, North Carolina, draws on architecture, sculpture, and functional art to create visually compelling and deeply personal works. Originally from Minnesota, she moved to Raleigh in 2013 to pursue graduate studies in architecture at North Carolina State University College of Design. As a licensed architect, her career took a sharp turn following a traumatic brain injury, which upended her life. This event led Redmann to turn to art as a means of healing, reshaping both her career and creative expression.

Her work, which spans from visually disorienting sculptures to acoustical art designed to address sensory overwhelm, is informed by her lived experience of navigating the world through the lens of disability. Inspired by the persistent visual disturbances she encounters daily, her pieces appear as if in motion, challenging viewers to see beyond the familiar and explore new ways of perceiving space and form. Her approach blends functionality with aesthetics, creating art that not only appeals to the eye but also serves as a tool for accessibility and sensory balance.

Here, Redmann shares how her personal journey has shaped her creative process and offers insights into the intersection of art and accessibility.

Eliza Redmann. Photography by Matt Ramey.

Get To Know Eliza Redmann Of Folded Poetry

Interior Design: Let’s start with the name of your studio, Folded Poetry. What do these words mean to you?

Eliza Redmann: Much like the aesthetic of my brand, the name Folded Poetry in itself is imaginative and thought provoking—it leaves much to be discovered. Does Folded Poetry mean the folding of a literal poem, or that the poetry somehow lies within the folds? Beauty lives in the questioning and pursuit of understanding, which tracks to the aesthetic of my brand where regular patterns are superimposed with a layer of geometric information which dares the mind to make sense of it. In this way both the name and aesthetic of Folded Poetry entice the mind of the beholder.

Redmann surrounded by her artwork Luminary, which is comprised of suspended laser-etched and cut iridescent acrylic. Photography by Matt Ramey.

ER: Prior to the car crash, my creative thinking was very much confined within the bounds of my architectural practice. I did not have a robust portfolio of art for art sake, and even during my years working as an architectural designer, I felt a lot of my creativity was left on the table. Post car crash and the resulting subdural hematoma, and after spending over a year coping with disabling chronic pain, nausea, fatigue, vision and balance issues, and perpetual overwhelm, it became clear that attempting to return to the profession of architecture was not in my best interest. I was unable to spend more than fifteen minutes at a time reading or doing other visually demanding work without feeling nauseated, hot, and overwhelmed. Having recently finished architecture graduate school with a clear picture of my life ahead, the loss of my profession was a terrible blow to my already bludgeoned morale.

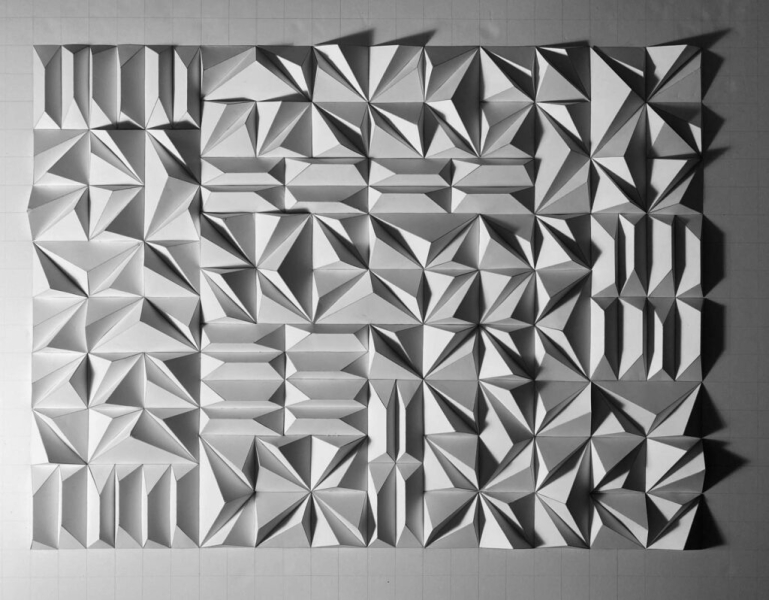

Instead of resisting my new reality, I took the time necessary to grieve, and from that space of self-acceptance a new idea was born – one which beckoned me to tap into my creative potential to reinvent not only my profession, but also my health, and life trajectory. The constraint of having very limited time on the computer before becoming symptomatic drove a creative outcome – the production of a small number of modular paper shapes which, when printed and assembled by hand, yielded complex geometric compositions. My new limitations forced me to work quickly and efficiently, and made perfectionism not an option. As a self identifying “completionist”, I was able to create a large volume of designs in a relatively short amount of time, leading to the launch of my design brand.

It’s surprising even to myself how long it took me to realize that my perplexing designs were representations of my visual disturbances which resulted from my brain injury. Often when I look at regular patterns—brick walls, tile floors, striped shirts—they appear to be “swimming” or moving on their own accord. My design aesthetic provides a visual experience akin to my own, challenging viewers in the way they encounter the art just as I myself am now challenged in health and my new daily reality.

Gold Dream, a free-mounted sculputral installation made of folded gold sheet acrylic that refracts light. Photography courtesy of Folded Poetry.

ID: How do you translate the “swimming” images you often see into sculpture and acoustical art? What materials do you gravitate to?

ER: Though short-lived, my experience in the field of architecture provided me with all of the tools necessary to translate ideas from small paper models into large-scale sculptural installations. Through my design school training I became familiar with the exploratory processes of material testing and prototyping. As I began creating larger scale sculptural installations, I produced as much as possible in-house, by myself. As demand has grown, I’ve learned that my offerings and impact can be greatly expanded by partnering with makers who already possess material-specific expertise. My architectural training allows me to understand their creation process and tailor designs to accommodate material constraints and limitations. Folded Poetry has now become larger than myself, and allows me to support fellow creators. I currently offer my modular sculpture designs at an architectural scale using acoustic felt, cast rockite, cast resin, and sheet acrylic. I’m very drawn to both wood and leather and am in the process of exploring their uses and capabilities as they pertain to Folded Poetry.

ID: What led you to pursue architecture, initially? What are some of your earliest memories of design?

ER: I witnessed my mother creating a variety of art during my youth: beautiful floral watercolors, a ceiling mural in my brother’s bedroom, custom Christmas ornaments featuring her unique handwriting. My creativity was always valued and cherished. As I grew into adolescence, I found great satisfaction in rearranging my bedroom, which I probably did a thousand times—trying new arrangements and adjacencies to get the flow of the space just right, only to decide a couple of months later that I needed something entirely new. I made the decision to pursue architecture while I was halfway through my undergraduate degree in Political Science. I was feeling uncertain about my future career path, and during that particular semester, I was working part-time at my campus art gallery where I met many featured artists and reinvented the gallery spaces over and over with each new show. I sensed an untapped wellspring of creativity bubbling up within me during my work in that position. My gallery assistantship overlapped with an environmental politics and policy class I was enrolled in where I learned about the importance of sustainable building design as a means of combating climate change. I chose architecture because it afforded me the opportunity to pursue my creativity through design while prioritizing my values of sustainability—all while standing up to my family’s academic achievement legacy.

My earliest memory of being deeply inspired by design was at the Mayo clinic in Rochester, Minnesota—I was eight years old and I was visiting my father who was dying from cancer. There were these fabulous blown glass sculptures by Dale Chihuly suspended from the atrium ceiling. Everything in my life was changing—I could feel it happening, completely out of my control—and I cherished the moments of looking up with wonder and awe and feeling some reprieve, if only for a few moments, during his final months of life.

Shell Dance made of folded paper board, a permanent installation in the artist-in-residence space at Cassilhaus. Photography by Matt Ramey.

ID: You’ve described your art as “a child of the pandemic.” In what ways did the pandemic shape your work?

ER: When the pandemic hit, I was already pretty isolated—trapped in pain and grappling with my new identity with disability post car-crash and brain injury. Suddenly I felt some kinship with others in our collective frustration that the world had changed, and not for the better. In a way, this triggered a renaissance moment within myself. There was no going back to how the world used to be, so I focused on accepting my new reality. One day, I just began creating within my altered realm of capability, and it was leaning into my new more limited scope of capacity which yielded creative outputs which were truly unique and impactful. Instead of resisting my limitations, I chose to create a new environment of self-acceptance which allowed me to truly thrive, and finally tap deep into that wellspring of creativity which was flowing under the surface waiting to be acknowledged. I consider the early paper sculpture designs I produced during that deep-pandemic period using my ink-jet printer and an exacto-blade to be the cornerstone of my brand, and I still reference them frequently in my work.

Diamond Dream comprised of folded cardboard with fabric veneer. Photography by Matt Ramey.

ID: Let’s talk about one of your recent collections. What led you to collaborate with Unika Vaev on acoustic products and what do you look for in a design partnership?

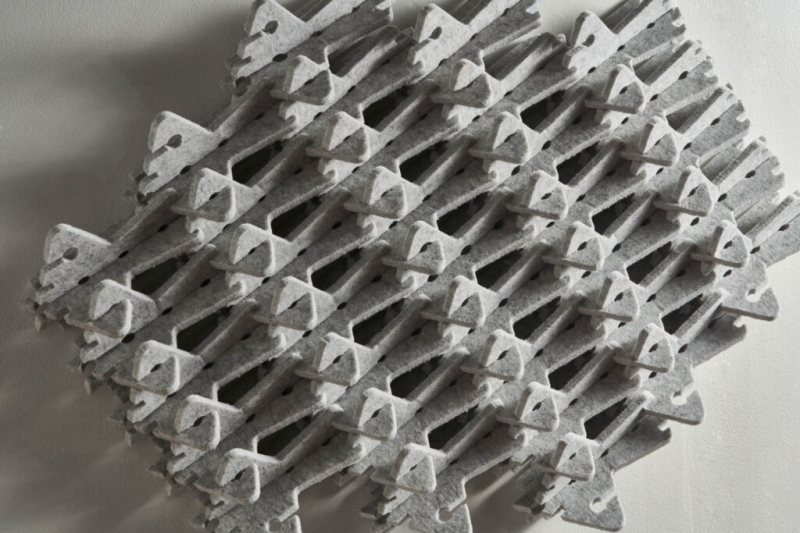

ER: During my experience working full-time as an architectural designer I found very limited options for acoustic products which were both beautiful and functioned at a high level. While creating my early paper sculptural explorations I was keenly aware that the directionally scattered surfaces of my designs had the potential to refract noise waves very effectively. My dream became pairing my Folded Poetry shapes with a noise absorptive material to bring my designs to an architectural scale through the development of a viable “acoustic art” solution unlike anything the industry has seen before. I began prototyping designs using noise absorptive materials and sharing them with my community via studio email newsletter. From there, I became connected with Unika Vaev, and together we recently launched our first collection of modular “acoustic art” titled simply Folded Poetry.

I seek design partnerships which require unique design thinking and/or innovation. I love identifying and working within parameters—be it a specific machine capability, an established sales stream for a specific product typology, or a prescribed material. I truly believe that constraint breeds creativity, and I thrive on adapting my designs to a variety of applications.

The Folded Poetry acoustic product line, a collaboration between Eliza Redmann and Unika Vaev. Renderings courtesy of Unika Vaev.

ER: I was unpleasantly surprised to find that, post-traumatic brain injury, the downtown repurposed rustic tobacco warehouses located in my city of Durham, North Carolina—my favorite hang-out spots filled with lasting memories—were now inaccessible to me. The reverberation and sheer audible volume which permeates the spaces was overwhelming at best and painful at worst. That loss of access to places, people, and experiences was deeply troubling, and fueled my acoustic artwork innovation and prototyping efforts. As I put my designs out into the world, they were received with such robust enthusiasm and delight. I was shocked to find myself in such abundant company in my condition—the sheer number of people who also struggle with auditory overwhelm and suffer from a loss of accessibility due to a lack of volume control prevalent in restaurants, bars, and gathering spaces of all kinds, is staggering. This discovery broadened my mission to include serving others by providing beautiful and noise-reducing art installations for the public to both enjoy and benefit from.

Epic, a paper artwork. Photography by Matt Ramey.

ER: Common neurological conditions are largely invisible, making it nearly impossible to recognize when a person is suffering from overwhelm or overstimulation. Indeed it is often difficult to recognize when the formerly stated are arising within oneself. Designing spaces to anticipate and mitigate this unintended response is an act of inclusivity. When I think about creating accessible spaces, the word “soft” comes to mind: soft volume, soft lighting, soft surfaces. Softness evokes the warmth of infancy and is comforting, healing, and inclusive.

Managing the volume of spaces is critical and so often overlooked despite the deep impact it has on the user experience and the willingness to become a repeat visitor. Lighting is equally as important – harsh overhead lighting is sneaky in that it can easily overwhelm the sensory system without you even realizing it’s happening. Simple consideration toward tailoring lighting to the specific uses of a space has the power to make it more accessible to the broader population. Providing a variety of spatial typologies including contained and comfortable private areas where folks can step-away and either recover from overstimulation, or simply seek reprieve from distraction, is an act of inclusive design. Within the build environment more broadly, clear wayfinding using symbols, colors, and clear language is an act of kindness and inclusivity.

The making of new geometric patterns. Photography by Matt Ramey.

ID: Do you consider your work as a form of activism?

ER: My work spreads awareness for invisible disability and provides both a window into understanding the lived experience of such, and a solution for managing the symptoms thereof—I do consider this to be activism.

Part of my work is designing a life which supports my creativity. I consider walking this path of self-actualization through creative entrepreneurship over one which would provide more perceived safety and stability to be an act of cultural resistance. Accepting yourself exactly how you are and showing up to create is activism. I hope that my work inspires people to think big about their capabilities and goals—I hope that they can look at me and say, “If she can do it, why can’t I?”

ID: What’s your dream project? If you could create anything, what would it be?

ER: I have so many dream projects—how to choose just one! A few include (but are no means limited to) creating mobiles, sculptural elements with integrated lighting, designing art for movie sets, creating inflatable stage art for bands, “assemble it yourself” sculptural wall kits geared toward broader accessibility, and last but not least, the creation of a business which empowers and uplifts others.

Pinch made from routed and bent HDPE plastic. Photography by Matt Ramey.

Wild Geese, folded paper on foam board. Photography courtesy of Folded Poetry.

Greyed Out made of landfill-averted acoustic felt. Photography by Matt Ramey.