Contents

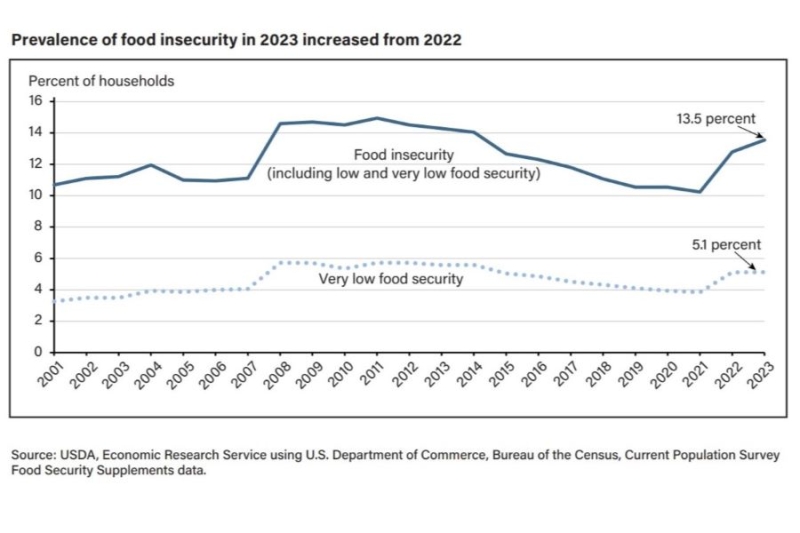

06 Sep 2024 — In 2023, 13.5% of US households (18 million households) were food insecure “at least sometime during the year,” according to the 2023 Household Food Security in the US report by the US Department of Agriculture (USDA). These households did not have access to enough food for an active, healthy life for all members. This is an increase of almost 5.5% from the 2022 level (12.8%).

The USDA estimates that 47.4 million people lived in food-insecure households in 2023, compared to 33.8 million people two years earlier.

In 8.9% of US households with children, children had food insecurity. Though this is similar to 2022 levels, it is a vast difference from 2021 (6.2% of households) and 2020 (7.6%). In 2023, 7.2 million children lived in households where at least one child was food insecure.

Meanwhile, very low food security rates remained similar to 2022 at 5.1%. This covers households where one or more members experience reduced food intake and disrupted eating patterns because of limited money or other resources for food.

Nutrition Insight discusses growing food security levels and examines root causes with the Center for Science in the Public Interest (CSPI), the Food Research and Action Center (FRAC) and Vitamin Angels.

“The US has invested in food safety net programs, but these programs cannot adequately address the factors that create poverty. Individuals with lower incomes face systemic political and structural barriers that limit financial resources and hence household food choices,” says Peter Lurie, CSPI president.

Joelle Johnson, CSPI deputy director, adds: “To truly reverse the trend of increasing food insecurity, the US needs to invest in more evidence-based policies that address root causes of the problem, for instance, economic support programs like the Child Tax Credit and guaranteed income.”

At least sometime during 2023, 18 million US households did not have access to enough food for an active, healthy life for all members.Confront root causes

FRAC is deeply concerned about the growing food insecurity. A spokesperson at the organization working to end hunger in the US points to the need to address root causes of food insecurity — “poverty, inadequate wages, lack of affordable housing, unaffordable healthcare and systemic racism.”

“These root causes have kept individuals and families in cycles of poverty and hardship for far too long, undermining their ability to access the nutrition they need to thrive,” the organization details. “Federal nutrition programs are critical, but to end hunger, we must address the underlying causes that keep so many people in the US hungry.”

“We must advocate for policies that create good jobs, fair wages and benefits, and pass anti-poverty programs, such as a permanent, expanded and inclusive Child Tax Credit, to lift more families out of poverty.”

Johnson details that structural racism and income inequality drive disproportionate rates of food insecurity. “Decades of unjust policies such as housing segregation, discriminatory hiring practices and voting restrictions have relegated people with racialized identities to lower generational wealth.”

“The US retail food environment is also an important driver of diet quality and choice. Inequitable access to healthy food environments and unequal exposure to unhealthy food marketing contributes to persistent differences in diet quality and health outcomes based on race, ethnicity and socioeconomic status.”

Growing prevalence

The recent increases in food insecurity follow a period of decreasing annual trends since 2014 after a period of high food insecurity during the recession that started in 2008 (14.6% of households).

“From 2011-2022, the rate of US household food insecurity slowly declined,” highlights Johnson. “However, the end of the COVID-19 public health emergency resulted in cuts to household SNAP benefits, a critical lifeline for families experiencing food insecurity and hunger.”

Trends in the prevalence of food insecurity and very low food security in US households from 2001 to 2023 (Image credit: USDA).“The impact of the SNAP benefit reduction coupled with high food prices means that more families are struggling to put food on the table. Research indicates that people experiencing food insecurity will sacrifice diet quality for quantity and in some cases will forgo meals to feed their families, further exacerbating food insecurity.”

At the same time, the USDA underscores that households were classified as having (very) low food security based on people experiencing food insecurity “at any time during the previous 12 months.” Food security prevalence may vary from day to day.

“Most households that reported experiencing food-insecure conditions during the previous 30 days reported experiencing the conditions between one to seven days during the month,” explain the authors.

Very low food security

USDA’s Economic Research Services used data from the annual Food Security Supplement, which was added in December to the monthly Current Population Survey conducted by the Bureau of the Census, part of the US Department of Commerce.

For each of the 30,863 participating households, one adult respondent answered questions that would indicate food insecurity during 2023, such as being unable to afford balanced meals, cutting the size of meals or being hungry because of too little money for food.

Households with very low food security reported multiple indications of reduced food intake and disrupted eating patterns due to inadequate resources for food. In contrast, households with low food security reported food acquisition problems and lower diet quality but typically reported fewer indications of reduced food intake.

Colleen Delaney, Ph.D., RDN, technical director for US programs at NGO Vitamin Angels, says it is “highly concerning that food insecurity prevalence continues to increase in the US and that very low food security remains consistent.” Vitamin Angels provides nutritional supplementation to pregnant women, infants and young children.

“Food insecurity can be chronic, acute or recurring — all of which have a huge impact on families and generations to come.”

Households with very low food security were worried that food would run out or said that bought food did not last.Most households with very low food security were worried that food would run out (98%), said that bought food did not last (97%), could not afford to eat a balanced meal (96%), skipped meals or cut the size of their meals (97%) or ate less than they should (93%).

Moreover, 30% of the 6.8 million households with very low food security reported that an “adult did not eat for a whole day because there was not enough money for food,” while 23% said this had occurred in three or more months.

Unequal access

Various population groups experienced statistically significantly higher food insecurity rates in 2023 than the national average for low and very low food security. These included households with children, including those with children headed by a single man or woman, households with Black, non-Hispanic reference persons or Hispanic reference persons and with incomes below the 100%, 130% or 185% poverty lines.

The report notes that food insecurity increased most for households without children, with more than one adult, an adult White, non-Hispanic reference person, households below 130% and at or below 185% of the poverty line, and those in metropolitan or suburban areas.

Of the US households with children, 17.9% or 6.5 million households were food insecure at some point in 2023. The report notes that parents and caregivers can often maintain (near-) regular diets and meal patterns for their children, even if the parents are food insecure. The authors detail that only adults were food insecure in about half of food-insecure households.

However, in 3.2 million households, both children and adults were food insecure. Moreover, in 1% of all households with children (374,000 households), food insecurity among children was so severe that “caregivers reported that children were hungry, skipped a meal or did not eat for a whole day because there was not enough money for food.”

Delaney from Vitamin Angels is concerned that households with children “remain at a similarly alarming rate of food insecurity” compared to 2022.

“This greatly impacts families and their health and ability to succeed in work and school. This report highlights the need for additional programmatic work and federal funding to ensure that those who are most vulnerable have adequate access to food and that both food and nutrition security is achievable for all US citizens.”

By Jolanda van Hal